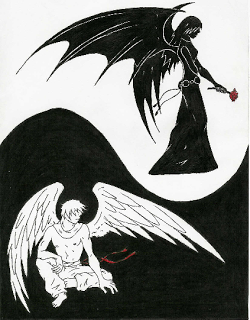

"Inside every man there is a struggle between good an evil that cannot be resolved," exclaims Homer Simpson. This wisdom echoes rabbinic discussions in the Talmud about the יצר טוב (yetzer tov), our good inclination, and the יצר הרע (yetzer hara), our evil inclination. The Jewish tradition teaches us that God imbued humankind with a healthy balance of good and evil. Each proclivity cannot exist without the counterbalance of the other. While we might gravitate to work towards a world bereft of evil inclinations, the rabbis advise us otherwise:

אלולי יצר הרע לא בנה אדם בית ולא נשא אשה ולא הוליד בנים", were it not for the evil inclination, a person would not build houses, would not marry, and would not bear children (Bereshit Rabbah 9:7).

A world without the yetzer hara's manifestations of competition, jealously, greed, sexuality, and anger also lacks the fundamental components of society: business, government, and procreation. Balance is the ideal, but we should never underestimate the power of the yetzer hara. Despite Homer Simpson's wise words about the coexistence of good and evil, he visualizes his evil inclination (Evil Homer) dancing over the tombstone of his yetzer tov (Good Homer), and shaking maracas singing: "I am Evil Homer, I am Evil Homer." The yetzer hara exists within all of us, and sometimes it flares up to tempt us into sinful action.

No one is immune from the yetzer hara, not even the most righteous of rabbinic sages in the Talmud. In fact, the rabbis teach that the most prominent figures in society are the most susceptible. "כל הגדול מחבירו יצרו גדול הימנו, the greater the person, the greater the evil inclination (B. Sukkot 52a)." This principle emerges most prevalently in relation to sexual sin. In tractate Kiddushin, the rabbis relate a series of stories about famous rabbis whose evil inclinations for sexual lust nearly or actually overpower their yetzer tov (B. Kiddushin 81a-b). Each tale offers a moral about understanding the yetzer hara within us.

- Rav Amram the Pious ascends a ladder* to proposition a group of beautiful women. Realizing he is about to give in to his temptation, he screams out "fire in the house of Amram!" By openly declaring his temptation, he is able to subdue his inclination, and create a group to support him in tempering his burning fire of lust.

- Rabbi Akiva has a tendency to mock sinners (people who give into their yetzer hara), so Satan decides to test him. Satan transforms himself into a beautiful woman atop a palm tree* to lure Akiva. As Akiva begins to climb the tree, Satan releases him from his grip. The story teaches us not to belittle the power of the yetzer hara, for no one is immune from it.

- Chiyah Bar Ashi** would pray for God to save him from his sexual yetzer hara. His wife overhears his prayer. Although a husband is required to provide for his wife sexually every week, the text tells us that he had not done so in a number of years. Chiyah Bar Ashi's wife decides to dress up like the town's famous prostitute Charuta.*** In seducing her husband, she deceives him into believing that he committed adultery; she also teaches an important lesson. Complete repression of the yetzer hara leads to its explosive and sinful manifestation.

We cannot escape the yetzer hara, nor should we try. God implanted within us both good and evil for a practical purpose. Life should be lived in a healthy balance of good and evil. Rav Amram (the man on fire) teaches later in the Talmud that no single day can pass without a person considering sinful thought (B. Baba Batra 164b). The important thing is to act in ways that favor our yetzer tov, while letting our yetzer hara remain only as an unfulfilled propensity.

Learn more about the Yetzer Hara at:

The Yetzer HaTov and the Yetzer HaRa Revisited

*The image of a ladder and the image of a palm tree appear to be sexual euphemisms for arousal.

**The name used here puns on the yetzer hara being both animalistic and a burning fire. חיה–animal. אש– fire.

*** The name חרותה, is another play on the idea of the yetzer hara being like fire. An English translation of this name might be "Hottie"

The Yetzer Hara and the Yetzer HaTov Revisited

One of the crowning achievements of Charles Darwin was the work on his theory of natural selection. According to Darwin, all animals in the world compete for resources, and only the fittest survive. Darwin believed that homo sapiens followed this same trend, and that in the struggle to survive, the strongest will always win. In such an arena of survival, ruthlessness and individualism conquer kindness and selflessness. But Darwin ran into a problem with applying this model to human beings, that is, all societies value altruism. Humanity esteems virtues of kindness, empathy, generosity, and humility––all vices when it comes to darwinian survival. Without moral virtues, we are just animals; and without primal instincts, we would all perish.

For millennium Judaism has viewed the balance of being virtuous and primal in the dichotomy of our having what it calls a יצר הטוב yetzer hatov, and a יצר הרע yetzer hara. A literal translation of these competing proclivities would be a good inclination and an evil inclination. But the tension within humanity isn’t between good and evil, but rather between our moral inclinations and our animalistic ones. To this end, the rabbis often project the yetzer hara as some kind of animal or beast. One talmudic tale tells of the rabbis who try to subdue the yetzer hara, which comes to them in the form of a fiery lion (גוריא דנורא) from the Holy of Holies (Yoma 69b). In another talmudic parable, a man named Chiyah Bar Ashi חייה בר אשי suffers from a persistent yetzer hara. His very name means “Beast son of Fire (Kiddushin 81b).” Animals are not a metaphor for evil (רע, but for the primal nature of man that is amoral.

Our yetzer hatov and our yetzer hara are not just inherent to who we are, but both are blessings of God upon us. The question is asked by Rabbi Nachman ben Shmuel as to how we can possibly call our yetzer hara (our evil inclination) “good.” The answer, is that were it not for the primal inclinations within us, humanity wouldn’t build, marry, procreate, and engage in business. Greed, lust, and ego are potentially harmful forces, but God’s world needs them to endure (Genesis Rabbah 9:7). Similarly, we should not that in the above talmudic tale (Yoma 69b), when the yetzer hara manifests in the form a fiery lion, it emerges specifically from the Holy of Holies. That is, the yetzer hara is a manifestaion of holiness. While we might call these inclinations “evil,” they are necessary evils in this world that, when tempered, drive the success of civilization. When left unchecked by our moral compass, the excess of these qualities breeds crime, fraud, war, inequity, and injustice. What sets us apart from the animal kingdom is that only humans can employ a moral conscience (our yetzer ha tov) to supersede our base instincts (our yetzer hara)

We like to paint individuals––either in real life or in literature––as heroes or villains. Jewish wisdom teaches that we are neither good nor evil, but rather that both a yetzer hatov and a yetzer hara that exists within each and every one of us. When Dr. Henry Jekyll, in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” figures out how to separate his primal inclination and his moral inclination into two separate beings, he creates a monster on the one hand, and a feeble wimp on the other. Living a purposeful and meaningful life requires that we are driven by a healthy balance between our moral and primal natures.